October 2025

Our Historic Mount Pleasant (HMP) Journal strives to inform community members by illuminating historic district building requirements, technical issues and solutions, and other aspects of the historic district, particularly its history.

Celebrating the Mount Pleasant Library Centennial

By Jonathan Herz

Last year, we celebrated the 100th anniversary of Mount Pleasant’s Bancroft Elementary School. This year, it’s our public library’s turn to celebrate. On the evening of Friday, May 16, 1925, the Mount Pleasant branch of Washington’s Public Library system, at Sixteenth and Lamont Streets, NW, was formally opened to the public to great acclaim.

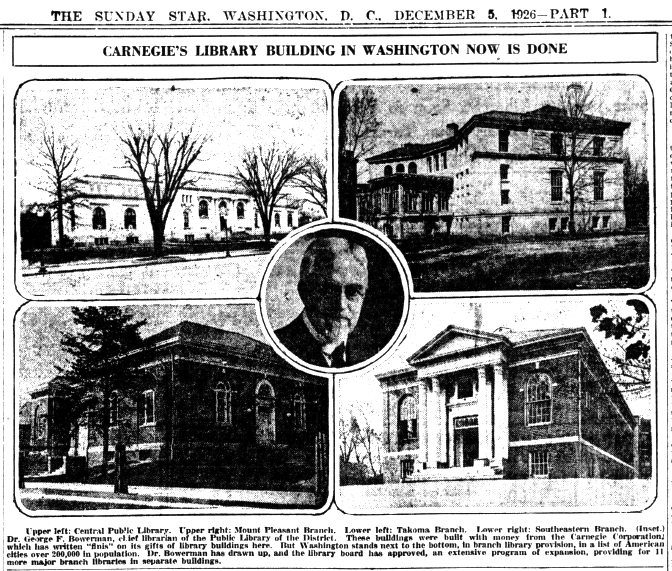

As The Evening Star wrote, “The Mount Pleasant branch now holds the distinction of ranking first on the list of the three [branch libraries] in architectural beauty, size and book capacity. The other branches are in Takoma Park and the Southeastern section of the city.”

Justice Wendall P. Stafford of the District Supreme Court (now the United States District Court for the District of Columbia) presided as the keys were presented in the name of the Carnegie Corporation (which had paid for construction); Edward L. Tilton, the architect; Mrs. John B. Henderson, from whom the library site was purchased; and the District government; to Dr. Frank W. Ballou, acting chairman of the committee on branch libraries. Reverend Dr. James H. Taylor, pastor of the Central Presbyterian Church, opened the ceremonies with an invocation.

Addresses were made by the head of the Federation of Citizens’ Associations, Mr. M. V. Lewis, retiring president of the Mount Pleasant Citizens’ Association, and the heads of the Columbia Heights, Kalorama, and Piney Branch Citizens’ Associations. Also speaking were a representative of the Twentieth Century Club (a benevolent society founded in 1890 by the women of All Souls Unitarian Church); the District Librarian, and Miss Margery C. Quigley, Mt. Pleasant branch librarian.

In his speech, the head of the Piney Branch Citizens’ Association said, “there never was a time in history when knowledge should be as accessible. A large number of persons in this country, including the Communists. I. W. W.’s [The Industrial Workers of the World, also known as the “Wobblies “] and others are constantly seeking to undermine the Government.” The Star wrote that the head of Kalorama’s Citizens’ Association observed that the presence of two members of the Federation of Citizens’ Associations’ Citizens Advisory Council “was an indication that citizenship in the District, though small, was gaining favor, indicating that some form of recognized and legalized representation was not far distant.”

The Twentieth Century Club representative “lamented the fact that the library was not to be more accessible to the children, at least until sufficient funds are available further to equip the building.” The children’s room did not open until a year later because Congress had cut the requested funding for a staff of twenty-one to twelve.

Dr. George F. Bowerman, the District Librarian thanked the Carnegie Corporation for doubling its original grant of $100,000 and Mrs. Henderson for her help in obtaining the site and for donating a painting, “The Grand Canyon” by Lucien W. Powell, to hang in the “browsing room.” He also emphasized the importance of a branch library in the northwest section noting that “The population exceeds 100,000, and is constantly growing with the erection of new apartments, dwellings and churches.”

Music preceding and throughout the program was provided by the United States Army Band Orchestra, L. S. Yassell, director. At the close of the ceremony, the building was “thrown open for inspection.”

Carnegie’s Libraries

Andrew Carnegie, once the richest man in the world, gave $56 million through his foundation, the Carnegie Corporation of New York, to build 2,509 public libraries around the globe, 1,681 of which were built in the United States. While most of the libraries were public buildings, 109 of them were academic libraries, including Howard University’s 1907 Carnegie Building.

Carnegie required grantees to provide the land, stock the library, pay the staff, and guarantee that the library would be free and open to all. He had a clear vision of what a library should be, including a large meeting space, children’s section and separate adult space. He also called for a professional librarian to provide reference services and keep an eye on the children. Carnegie also believed, writing in 1903 to the head of the Philadelphia Free Library, that $50,000 was the minimum they should be spending for each of their branch library buildings.

Four public libraries were built in Washington using Carnegie funds. In 1899, Carnegie agreed to donate $250,000 for the first library after a chance encounter with the president of the D.C. library trustees while waiting to see President Theodore Roosevelt at the White House. By the time the first public library building in D.C. opened in 1903, construction costs had risen by $100,000 – which Carnegie also covered. The central library’s dedication was attended by President Theodore Roosevelt and Carnegie, who offered $350,000 for new branch libraries throughout the city. But, the required congressional approval to accept donated money for the branches was slow to come.

It took Congress seven years to act on Carnegie’s offer, finally funding site acquisition for the first branch library, which opened in Takoma Park (now called Takoma) in 1911 using $40,000 of Carnegie funds. After Takoma opened, the library on Mt. Vernon Square was renamed Central Public Library.

Ten years after construction of the Takoma Park branch, Congress approved $8,360 to purchase the site for the third branch library, Southeastern, near the Eastern Market. Although the Corporation discontinued its library construction program after Carnegie’s death in 1919, it agreed to provide $67,000 to build the library, which was designed by architect Edward L. Tilton who later designed the Mt. Pleasant library.

Tilton later won the American Institute of Architects’ Gold Medal for excellence in public work and designed more than one hundred libraries in the United States and Canada.

Today, the D.C. Public Library has 26 branch library locations throughout the city.

The Mount Pleasant Library

The Mount Pleasant Library was the final D.C. branch to be built with funding from the Carnegie Corporation, which pledged $100,000 – double his recommended minimum amount for Philadelphia branch libraries – for its construction in June of 1922.

On December 4, 1922, the annual budget sent to Congress asked for $25,000 to purchase the library site and authorize the District Commissioners to accept the $100,000 from the Carnegie Corporation.

Then, on January 3, 1923, Texas Representative Thomas L. Blanton, a member of the House District Committee and Mt. Pleasant resident, had the item eliminated from the District appropriation bill, saying that people in other parts of the country “ought not to be taxed to pay for the branch library or site in Mount Pleasant.”

Representative Louis C. Cramton of Michigan tried hard to have the item retained, saying, “The site proposed, I am reliably Informed, is worth at least $50,000. It is offered to the District for $25,000… The building will be entirely at the expense of the Carnegie Corporation, so that the $150,000 site and building will cost the people of the District only $25,000, of which, under this bill, only $10,000 will be the part of the United States… I hope the gentleman will not insist.” Finally, on February 28. 1923, Congress appropriated $25,000 for the site, which Mrs. Henderson generously sold to the Government at half price, in consideration, as she said, “of the fact that this branch library will be a large and beautiful building.”

The architect, Edward L. Tilton, designed the building in the Italian Renaissance style clad in Indiana limestone to harmonize with the monumental mansions and churches lining 16th Street. By the time it was completed three years later, construction costs, like that of the Central Public Library, had risen dramatically. The Carnegie Corporation covered the additional $100,000 needed, making the Mt. Pleasant library’s final cost four times Carnegie’s recommendation for a single library in Philadelphia.

The Mt. Pleasant branch library opened with about 11,000 books and 100 magazines. Appropriations of $40,000 over the next two years were expected to vastly increase those numbers. At its opening, because of understaffing, only the main floor was opened and restricted to adults and high school students.

The library’s design was a great success.

After its opening, the Sunday, May 17, 1925 Washington Post wrote,

“To one passing the building at night the library looks like some fashionable clubhouse, with its long windows, its mellow lights and its dignified proportions. Within, the comfortable chairs and the general atmosphere of intellectual activity, the Powell painting of the grand canyon, presented by Mrs. John B. Henderson, and the gay, fresh bindings all contribute to the effect.”

A special feature of the design was the children’s library on the second floor which boasted its own private entrance stair on the western facade. Also notable on the South side was an outdoor reading room known as the “Sun Room,” which was intended to be closed in winter with “great windows,” but eventually, was enclosed year-round. The Sun Room was demolished in 2009 to make way for the new entrance between the original building and the new addition.

As one of four public libraries and the second largest branch in D.C., Mount Pleasant served most of the northwest part of the City, and its large meeting room in the basement provided a popular venue for civic and cultural meetings, as well as annual city-wide spelling bees. The room, which seated about 100, was the setting for a great number of local literary, drama and citizens organizations, including both the Mount Pleasant and Columbia Height Citizens’ associations. A film festival was inaugurated in 1964 and, in the 1970s, there was a family film night. Today the renovated basement houses the stacks and a small meeting room, with a larger meeting room in the new addition.

For a great account of contemporary social and cultural events in 1925, at the time of the library’s opening, see the D.C. Public Library’s website, Mt. Pleasant Library Celebrates 100 Years.

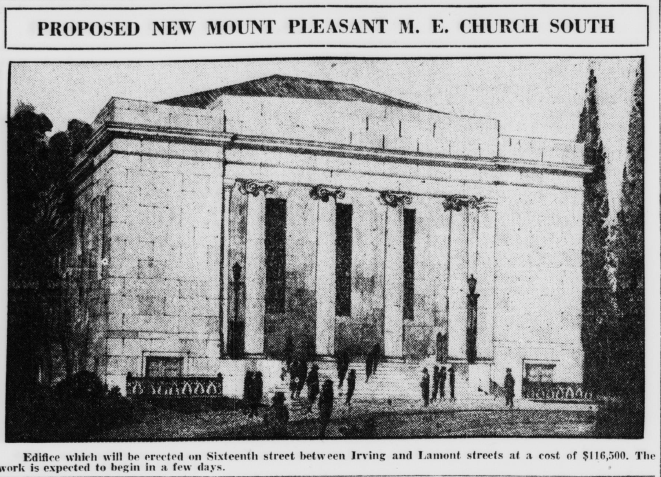

The “large and beautiful” library matched the grandeur of other buildings on 16th Street and inspired the redesign of the modest, brick Mt. Pleasant Methodist Episcopal Church South, a few doors down. The July 9, 1927 Evening Star described the church’s façade as “a front of massive dignity in harmony with other imposing buildings in this section of Sixteenth street.”

Over the years, the library adapted to shifting neighborhood demographics and patron needs.

During the Great Depression, local artist Aurelius Battaglia, under Roosevelt’s Public Works of Art program painted the “Animal Circus” murals in the children’s reading room. Battaglia later worked for Disney Studios on Dumbo and Pinocchio.

The new Mount Pleasant library branch was a great success, with circulation growing from 155,000 volumes in its first year to a peak of 442,000 in 1937–1938. After the Petworth Branch opened in 1939, circulation fell to 250,000. By 1954, circulation had declined to 177,000 volumes. A report that year cited the 1953 opening of the Cleveland Park Library as the major reason but also listed the lack of parking, an increase in bus fares, and a “changing neighborhood.” The 1957-1958 annual report talked of “neighborhood blight” with low income and often transient families replacing middle income ones.

By 1970, library reports described the community as predominantly low-income elderly white residents, a majority Black population and growing numbers of Spanish-speaking immigrants with limited formal education. In response, the library expanded its Spanish-language collection and hired Cuban immigrant Alberto Irabien as an advisor and librarian to assist Hispanic residents.

The 1980s brought severe funding cuts, reducing staff by over half and closing the children’s room. Renovations in 1984 modernized and made the building handicapped-accessible, revitalizing use. By 1986, circulation and visitor counts had doubled, but circulation began to decline again to fewer than 50,000 items annually in 2004. After that, circulation began growing again to reach more than 78,000 items in 2007.

In 2008, the D.C. Public Library (DCPL) launched a major initiative to renovate, restore, and expand the branch to update accessibility, vertical circulation, infrastructure, improve code compliance, and add high-speed Internet access and new computers, among other things. DCPL’s building program acknowledged that the Library was located in an historic district, but did not address the requirement that exterior changes had to comply with the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation, which require that any “addition should be designed to be compatible with the historic character of the building… the massing, size, scale, and architectural features to protect the historic integrity of the property and its environment.”

CORE Group, in partnership with HMA2 Architects, were selected for the design. The first conceptual design in October 2008 included a glass-fronted box occupying the entire west yard on Lamont Street and a switchback ramp to the main entrance. At the February 2009, Commission of Fine Arts (CFA) meeting, “Commission members expressed disappointment with the proposed form and architectural language of the addition, which they characterized as too aggressive, unsympathetic to the historic building…” Instead, they recommended that “the addition be quieter and more supportive of the historic building.”

Following a long series of meetings with the community, the D.C. Historic Preservation Office and the CFA, significant design changes were made: moving the new addition behind the original building and placing the ramp along the property line to a new entrance at an atrium between the original and new buildings. The grand, original entrance on 16th St. became an emergency exit. The renovated library reopened Sept. 12, 2012.

Over the past century, the Mount Pleasant Library has continually adapted to profound changes in its surrounding community, evolving from a largely middle-class, white patron base to amply serve the increasingly diverse, international library community that Mt. Pleasant has become.